# The Vital Role of Green Spaces in Urban Living

Written on

Chapter 1: Why Green Spaces Matter

The significance of parks, trees, and green areas within urban settings cannot be overstated.

Photo by Hector Argüello Canals on Unsplash

In recent years, there has been a movement to integrate more nature into cities. Reactions vary; while some embrace this trend, others criticize it as a waste of resources. But why is this important? For the majority of our evolutionary journey, humans thrived in natural surroundings. The urban landscapes we recognize today have only emerged in the last hundred years. Notably, over 56% of the global population now resides in urban areas—a figure projected to rise to 68% by 2050 according to the U.N. [1].

City living offers numerous advantages, such as accessibility to schools, healthcare, and shops. However, the demand for these services often leads developers to prioritize construction over green spaces, resulting in cities dominated by concrete and glass.

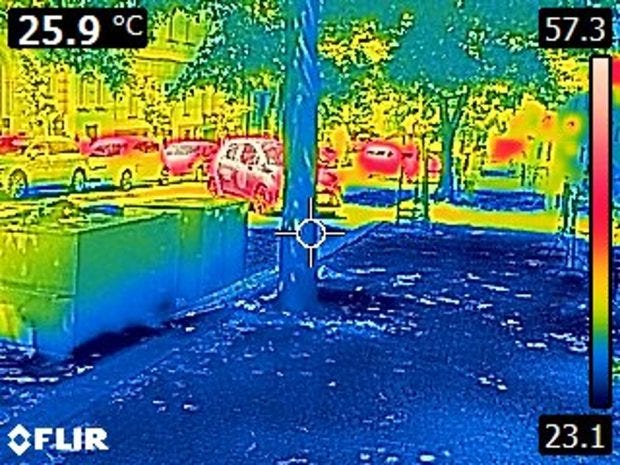

Urban Heat and Climate Extremes

This shift away from natural landscapes has significant implications for local climates. Urban areas can be 1 to 10°C warmer on average than rural ones due to the urban heat island effect—where materials like asphalt and concrete absorb heat rather than reflecting it [16]. As urbanization escalates, we also witness an uptick in severe weather events, including heatwaves, droughts, and flash floods. This is largely due to poorly designed urban environments that lack sufficient greenery. Parks, gardens, and trees should be integral components of urban planning, not just afterthoughts.

To address climate-related challenges, we must integrate trees and vegetation into every aspect of urban design.

Benefits of Green Spaces

The advantages of incorporating greenery into urban settings are multifaceted:

Enhancing Air Quality: Plants play a crucial role in filtering air pollutants. They absorb certain particles and trap others, which are then washed away by rain.

Climate Regulation: Trees influence airflow, providing cooling effects through shade and transpiration. The temperature differences between shaded and sunlit areas can be substantial.

Photo by The Charles University Faculty of Mathematics and Physics

Water Management: Tree canopies catch rainwater, allowing for absorption and evaporation. This helps mitigate storm impacts and reduce erosion.

Biodiversity Support: Green spaces provide vital habitats and food sources for various species, enhancing urban biodiversity.

Health Benefits of Nature

Humans have spent the vast majority of their evolution in natural environments, and modern urban settings often do not cater to our psychological needs. Research suggests that spending time in nature can alleviate mental fatigue and enhance our ability to concentrate [2].

Recent studies have highlighted various ways that nature positively impacts health:

- Stress Reduction: Exposure to natural settings promotes relaxation and improves well-being, lowering stress indicators such as blood pressure [3].

- Emotional Well-being: Time spent in nature correlates with improved mood and reduced feelings of anxiety and depression, particularly in stressful situations [4][7].

- Post-surgery Recovery: Patients with views of natural landscapes from their hospital rooms tend to recover faster and require fewer pain medications compared to those with views of urban structures [5].

- Mental Health: Green environments are being explored as therapeutic spaces for conditions like ADHD [6].

- Physical Activity: Proximity to parks and green areas encourages physical activities like walking and cycling, which can combat obesity [8][9].

- Cancer Prevention: Some studies indicate that living in greener areas may be linked to lower risks of certain cancers [10].

Impact on Child Development

The benefits of green spaces extend to children even before birth. Research shows that access to greenery is associated with better birth outcomes and maternal health [11].

Parents often note that children who engage with nature exhibit improved mental and physical health. Unstructured outdoor play fosters physical strength and develops essential social and emotional skills [12]. Notably, exposure to natural environments can lower autism prevalence and reduce the risk of psychiatric disorders later in life [13][14]. Furthermore, a study found that increased greenery in neighborhoods was associated with higher IQ scores in children [15].

Investing in green spaces is not just beneficial; it is essential for our future and that of the next generations. Cities and investors should prioritize these initiatives. By increasing tree cover in parks, creating green roofs, and planting along sidewalks, we can cultivate urban environments that resemble the natural beauty of places like Singapore.

Photo by Victor on Unsplash

Chapter 2: Understanding Urban Green Spaces

This video highlights the crucial role of urban green spaces in promoting sustainability and enhancing quality of life in cities.

Here, we explore the concept of a green city and the various benefits of integrating nature into urban planning.

References

[2] Kaplan, S. The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward an Integrative Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [3] Kondo, M.C.; Jacoby, S.F.; South, E.C. Does Spending Time Outdoors Reduce Stress? A Review of Real-Time Stress Response to Outdoor Environments. Health Place 2018, 51, 136–150. [4] Morita, E.; Fukuda, S.; Nagano, J.; Hamajima, N.; Yamamoto, H.; Iwai, Y.; Nakashima, T.; Ohira, H.; Shirakawa, T. Psychological Effects of Forest Environments on Healthy Adults: Shinrin-Yoku (Forest-Air Bathing, Walking) as a Possible Method of Stress Reduction. Public Health 2007, 121, 54–63. [5] Ulrich, R.S. View through a Window May Influence Recovery from Surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [6] McCormick, R. Does Access to Green Space Impact the Mental Well-Being of Children: A Systematic Review. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2017, 37, 3–7. [7] Sarkar, C.; Webster, C.; Gallacher, J. Residential Greenness and Prevalence of Major Depressive Disorders: A Cross-Sectional, Observational, Associational Study of 94 879 Adult U.K. Biobank Participants. Lancet Planet. Health 2018, 2, e162–e173. [8] Coombes, E.; Jones, A.P.; Hillsdon, M. The Relationship of Physical Activity and Overweight to Objectively Measured Green Space Accessibility and Use. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 816–822 [9] Beyer, K.M.M.; Szabo, A.; Hoormann, K.; Stolley, M. Time Spent Outdoors, Activity Levels, and Chronic Disease among American Adults. J. Behav. Med. N. Y. 2018, 41, 494–503. [10] Datzmann, T.; Markevych, I.; Trautmann, F.; Heinrich, J.; Schmitt, J.; Tesch, F. Outdoor Air Pollution, Green Space, and Cancer Incidence in Saxony: A Semi-Individual Cohort Study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 715. [11] Fong, K.; Hart, J.E.; James, P. A Review of Epidemiologic Studies on Greenness and Health: Updated Literature through 2017. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2018, 5, 77–87. [12] Kahn, P.H.; Kellert, S.R. Children and Nature: Psychological, Sociocultural, and Evolutionary Investigations; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; ISBN 978–0–262–25012–2. [13] Wu, J.; Jackson, L. Inverse Relationship between Urban Green Space and Childhood Autism in California Elementary School Districts. Environ. Int. 2017, 107, 140–146. [14] Engemann, K.; Pedersen, C.B.; Arge, L.; Tsirogiannis, C.; Mortensen, P.B.; Svenning, J.-C. Residential Green Space in Childhood Is Associated with Lower Risk of Psychiatric Disorders from Adolescence into Adulthood. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 5188–5193. [16] Masson, V; Lemonsu, A.; Hidalgo, J.; Voogt, J. Urban Climates and Climate Change. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 2020, 45, 411–444.