The Historic 1907 Race from Beijing to Paris: A 10,000-Mile Journey

Written on

Chapter 1: The Beginning of an Epic Journey

In the year 1907, automobiles were still a novelty, primarily associated with the affluent. For the average person, the notion of driving a car was as unimaginable as traveling to work in a spacecraft. At that time, vast areas of the world remained steeped in a feudal-like existence, particularly in places like China and Russia, where many were akin to medieval peasants. Yet, in this year, some of these "modern peasants" gathered along dusty roads, eager to witness the spectacle of sleek, futuristic vehicles racing towards glory.

Five racing teams, comprising twelve individuals in total, set off from Peking (now Beijing) with the ambitious goal of covering 9,000 miles to reach the French capital, Paris. Even in today’s context, such a feat would be daunting and would likely be tailored for television. With contemporary vehicles and meticulously charted routes, traversing some of the globe's most desolate regions would still prove arduous. Now, consider the challenge of undertaking this journey in 1907.

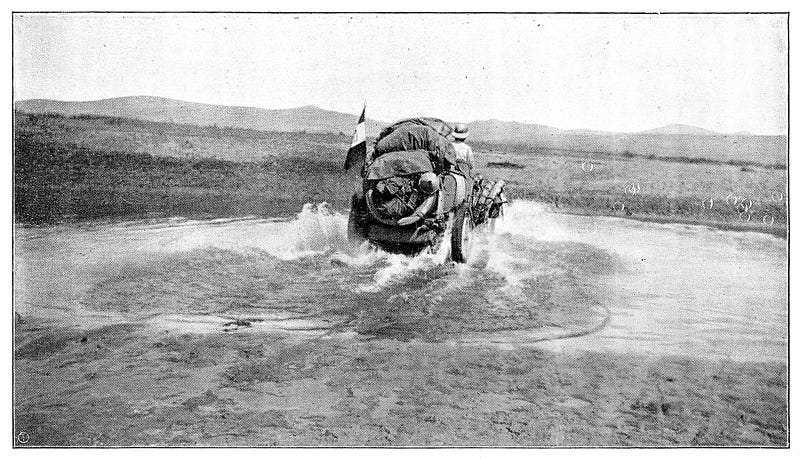

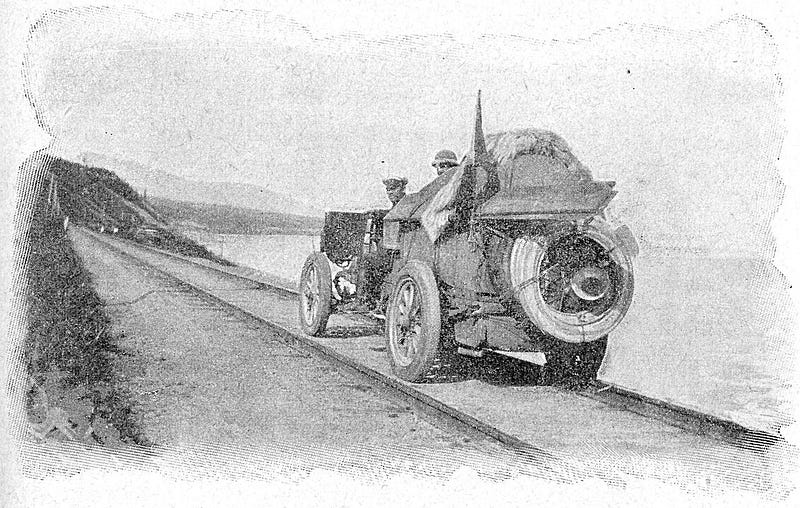

The landscape of 1907 was vastly different from today’s world. Infrastructure was not geared towards vehicles; roads were predominantly designed for foot traffic or horse-drawn transport. Fuel stations were nonexistent, and accommodations were sparse. A simple flat tire could spell disaster, as replacements could be hundreds of miles away. Yet, these were the conditions accepted by the brave drivers who invested considerable sums to transport their vehicles to the starting line in Beijing.

Chapter 2: The Spark of Adventure

The race was inspired by a casual newspaper piece that encouraged drivers to embrace the new automobile technology to explore the world and pursue greatness. The article proclaimed:

"What must be demonstrated today is that with a car, a person can achieve anything and travel anywhere. Who will take on the challenge this summer to journey from Paris to Peking by automobile?"

Eager to showcase the enduring spirit of exploration, several Europeans seized the opportunity. Despite the newspaper's subsequent retraction and attempts to halt the race, five teams chose to accept the challenge proposed by Le Matin.

The undertaking was as wild as one might expect. Among the five teams, three hailed from France, one from the Netherlands, and one from Italy. The Italian entry was led by the eccentric prince, Scipione Borghese, who, while supposedly behind the wheel, often had his chauffeur do the actual driving.

The participating vehicles were not brands recognized today. The prince drove an Italian Itala, while the French teams utilized two DeDions and a Contal, the latter being a three-wheeled cyclecar. The Dutch team was behind a Spyker, a manufacturer that would ultimately collapse in 1926.

With no established rules, the race’s objective was straightforward: the first vehicle to reach Paris would claim victory. The route generally adhered to the telegraph lines winding through Central Asia, as there were few roads and even fewer maps. To facilitate fuel access, camels were dispatched ahead to leave cans of fuel along the way. Gas stations were a luxury not available to these racers.

Incredibly, four out of the five teams completed the grueling race despite numerous challenges.

Chapter 3: Triumph Against All Odds

The Italian team, led by Prince Borghese, emerged victorious, despite his penchant for detours—including a significant diversion to St. Petersburg for a noble dinner, which was hundreds of kilometers off course. The Italian team’s success can be attributed to the superior performance of their Itala, boasting a seven-liter engine, making it both faster and more durable than the competition.

At the time, many speculated that the heftier Italian vehicle would falter on rugged terrain, whereas the French teams believed their lighter cars would excel on unpaved paths. The unpredictability of the race was emblematic of early motorsport, characterized by a blend of mystery and conflicting theories that could only be validated through competition.

Charles Godard, leading the Dutch team, surprisingly finished second. He had no funds and spent every last penny transporting his borrowed car from Europe to China. To survive the journey, Godard resorted to deception and trickery, fabricating stories to secure food and fuel. Ultimately, he was arrested for fraud after the race concluded.

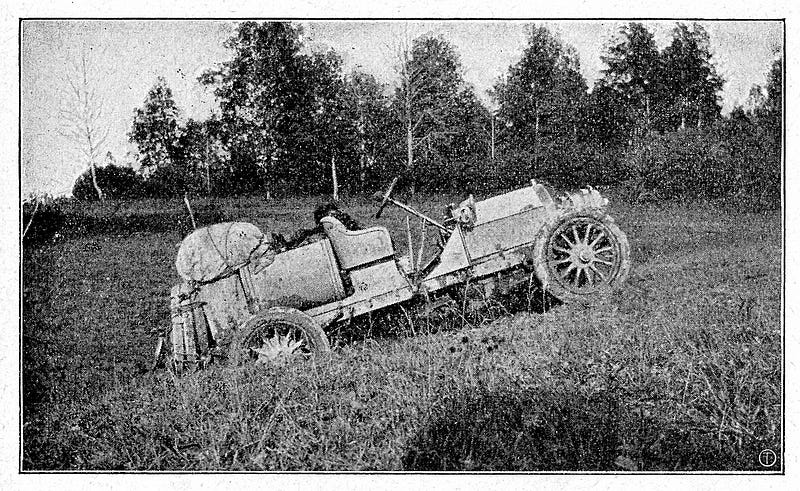

The vehicles faced significant obstacles due to roads that were often ill-suited for automobiles. Some routes had never been traversed by a car before, leading to unfortunate incidents. One French team, driving the poorly equipped Contal, became stranded in the Gobi Desert and narrowly avoided death before being rescued by local inhabitants.

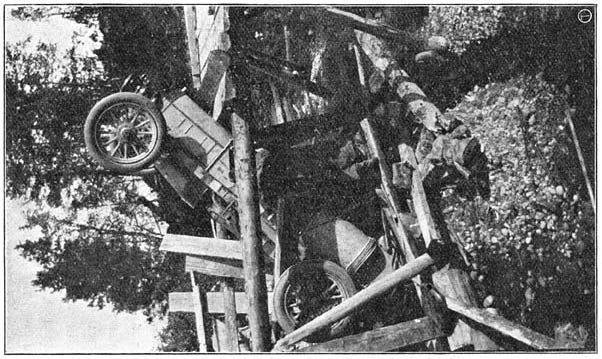

Even the winning car faced peril when it plunged through a bridge built for mules, not cars.

Chapter 4: A Legacy Documented

Remarkably, the racers documented their journey extensively, bringing along a cadre of reporters who utilized the telegraph to provide near real-time updates. Given that the challenge originated from a French publication and three of the five teams were French, there was widespread outrage in France when the Italians led for most of the race and ultimately clinched victory. The Dutch team’s second-place finish, piloted by a fraudster, added insult to injury, as the French teams placed third and fourth, with one team not finishing due to their near-fatal experience in the Gobi.

Since that historic race in 1907, numerous attempts have been made to replicate the event, yet none have managed to recapture its original spirit. In today’s world, such grand and spontaneous challenges are a rarity.

For those interested in further insights, one of the reporters published a contemporary account titled La Metà del Mondo Vista da Un’automobile (Half The World Seen From an Automobile), available in Italian for free, featuring a multitude of captivating photographs.

The first video presents "Peking to Paris: 1907's 8,000-Mile Race That CHANGED The World," offering an engaging exploration of this monumental event.

The second video titled "Peking - Paris 1907" provides additional insights and reflections on the historic race.