Exploring the Connection Between Eye Movements and Brain Activity

Written on

Chapter 1: The Science Behind Eye Movements

Rapid and random eye movements during sleep may be linked to increased temperature in areas of the brain that connect with the eyes, or possibly to the erratic behavior of molecules within those regions.

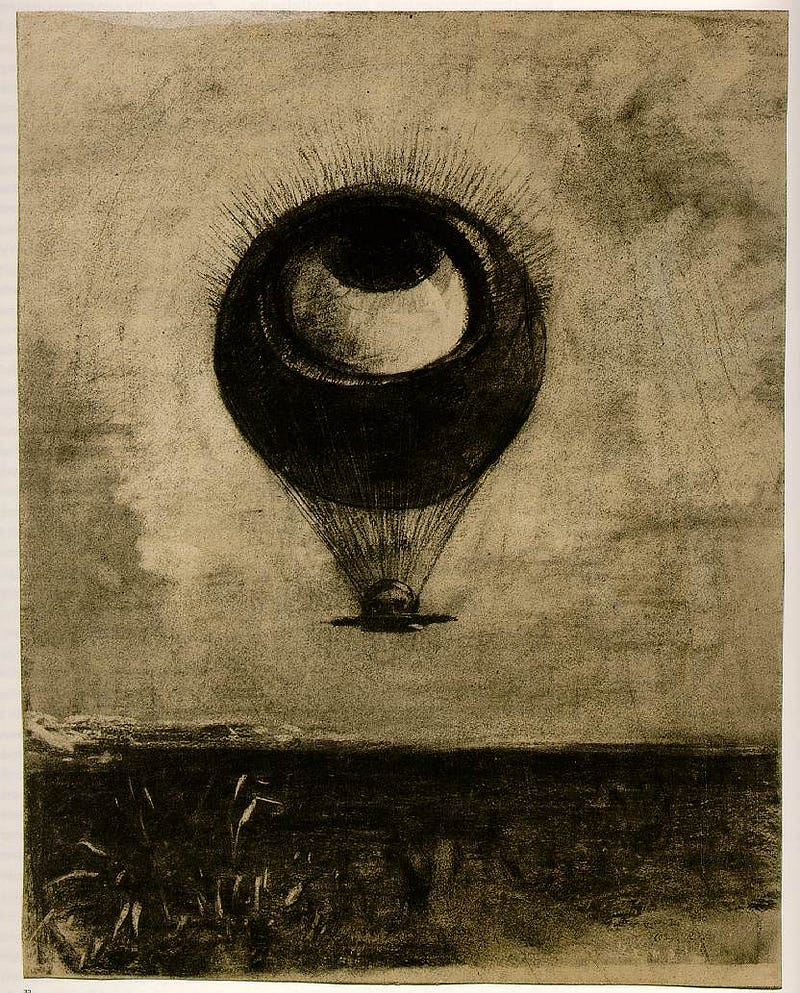

The artwork "Eye Balloon" by Odilon Redon. Image sourced from WikiArt. Public domain.

For over five decades, it was believed that only mammals and birds experienced distinct neurological sleep phases. However, groundbreaking studies have now revealed that reptiles, fish, fruit flies, octopuses, and various invertebrates exhibit sleep states with similar characteristics.

— Jaggard et al., “Non-REM and REM/Paradoxical Sleep Dynamics Across Phylogeny” (2021)

Section 1.1: Brain Temperature and REM Sleep

The brain of an animal undergoes temperature fluctuations throughout different time intervals. As we awaken and engage in daily activities, the brain slightly warms up, becoming more fluid, dynamic, and expansive. Conversely, during sleep, it cools down, adopting a more solid, orderly, and compact state. Throughout the night, during periods of dreaming and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, the brain heats up repeatedly and cools during deeper slow-wave sleep phases.

It appears likely that the temperature of the brain plays a significant role in causing the rapid and random movements of the eyes during REM sleep. Several factors support this idea. The rapidity and randomness of these eye movements are indicative of increased temperature in liquid crystalline substances, such as those found in the brain. If the movements were solely rapid, one might theorize a connection to faster molecular motion in brain regions linked to the eyes. The additional randomness, however, strengthens the possibility of a causal relationship.

If this theory holds, it suggests that variations in brain temperature might influence external behaviors in animals. Given the close connection between the brain and the eyes, it’s reasonable to assume that minor neural activities could be mirrored in eye movements.

This concept doesn't exclude the possibility that similar effects could manifest in other body parts. Rapid and random elements can also be observed in phenomena such as seizures, laughter, dancing, and singing, all of which may correlate with localized or general increases in brain temperature. For instance, research indicates that the tempo of songs in male zebra finches correlates with elevated brain temperatures when females are present (Aronov and Fee 2012).

Subsection 1.1.1: The Universality of Sleep

Jaggard et al. (2021) present evidence that all animals experience sleep, even those without brains. They note that “REM-like activities” can be observed in “reptiles, fish, flies, worms, and cephalopods.” This underscores the biological significance of sleep and REM, regardless of the exact processes occurring in the brain.

The occurrence of random eye movements does not necessarily imply a function specific to the eyes themselves, and the early evolution of REM in the animal kingdom does not fully account for its continued presence. Nonetheless, it is likely that a shared characteristic in the brains of most animals accounts for the phenomenon of sleep and REM. Given that sleep-like activities have been observed in brainless organisms like hydras (Jaggard et al. 2021), a potential explanation for rapid eye movements may lie in universal properties of nervous systems, such as liquid crystallinity and temperature fluctuations.

Chapter 2: Insights from Research

The first video titled "Eye Movements and Brain Function" delves into the intricate relationship between eye movements during REM sleep and underlying brain activity.

The second video, "Understanding Eye Movements for Brain," offers further insights into how these eye movements might reflect brain processes during different sleep phases.

Works Cited

Aronov, Dmitriy, and Michale S. Fee. “Natural Changes in Brain Temperature Underlie Variations in Song Tempo During a Mating Behavior.” PloS one 7.10 (2012): e47856.

Jaggard, James B., Gordon X. Wang, and Philippe Mourrain. “Non-REM and REM/paradoxical sleep dynamics across phylogeny.” Current Opinion in Neurobiology 71 (2021): 44–51.