The Unsung Pioneer: Rosalind Franklin and the DNA Mystery

Written on

Chapter 1: The Beginnings of a Trailblazer

In the early 20th century, the scientific field was predominantly male. However, Rosalind Franklin's father championed her education by enrolling her in one of the rare schools in London that offered physics and chemistry to girls. This opportunity ignited her passion for science, leading her to excel academically.

After completing her studies with top honors, Franklin pursued a scientific career. At just 18, she entered the University of Cambridge as a non-degree student in 1938. Although she was allowed to audit courses and conduct research, the institution did not grant degrees to women at that time. It wasn't until three years after her departure that Cambridge retroactively awarded her a doctorate, backdating it to 1945.

Despite her capabilities, many of her male peers dismissed her contributions, seeing her merely as an attractive figure rather than a serious scientist.

Section 1.1: A New Chapter in Paris

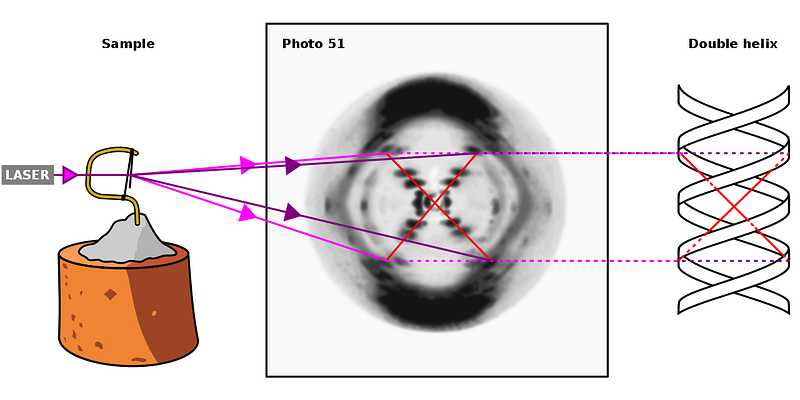

After her time at Cambridge, Franklin relocated to Paris to study under a leading expert in x-ray crystallography. This advanced technique allowed her to analyze microscopic structures that were invisible to light microscopes. While she flourished in the collaborative environment of France, her return to London brought isolation and disappointment as she struggled to find a supportive network.

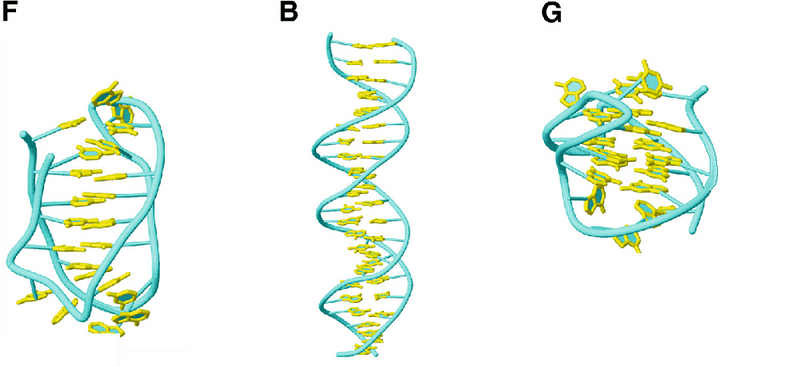

Franklin's innovative method of surrounding samples with hydrogen prepared her for a groundbreaking investigation into DNA. However, the substance's elusive nature, changing shape depending on its surroundings, proved to be a significant challenge.

Through a lengthy series of trials, Franklin achieved a breakthrough, capturing what she called "Photo 51" after numerous attempts. This pivotal image would later play a crucial role in understanding DNA's structure.

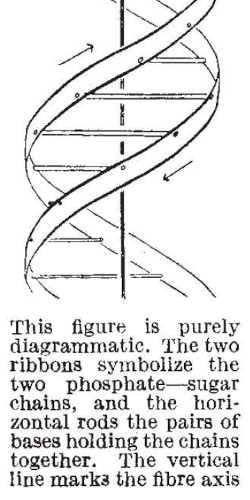

In 1951, she shared her findings at a King’s College seminar, where she challenged the prevailing belief in a single helix structure of DNA. Unfortunately, her insights went largely unacknowledged by her male colleagues.

Chapter 2: The Race for Discovery

Fifteen months later, James Watson and Francis Crick began their quest to uncover DNA's structure. Watson had attended Franklin's earlier lecture but recalled only her appearance, failing to recognize the significance of her research. By then, Franklin had already discerned that DNA's structure was likely a double helix but needed to confirm its exact chemical composition.

Despite her capabilities, she faced mounting frustration in a male-dominated environment that forced her into solitude. Her collaboration with John Desmond Bernal, an Irish scientist open to working with women, led her to shift her focus to nucleic acids.

In 1953, during a visit to King’s College, Watson stumbled upon Franklin's Photo 51. His excitement was palpable, marking a turning point in their research. Just three months later, Watson and Crick published their paper in Nature, earning them a Nobel Prize.

Watson and Crick's paper lacked substantial evidence for their double helix model, merely suggesting its likelihood and deferring detailed analysis to future publications. They invited Franklin to review their work, recognizing they needed her data to bolster their claims. Franklin quickly produced a comprehensive paper detailing the DNA structure based on her rigorous research.

Despite her monumental contributions, Franklin's life was tragically cut short when she died of ovarian cancer in 1958 at the age of 37. Her extensive exposure to x-rays during her research likely contributed to her illness.

On the day of her passing, she was set to unveil a new method for studying viruses. Her colleague Aaron Klug continued her work and later received a Nobel Prize for his advancements in viral imaging.

Franklin's status as an unmarried woman further fueled the disdain of her male colleagues, who could not fathom a woman dedicated solely to science. Though her research underpinned two Nobel Prizes, her name was conspicuously absent from their acceptance speeches.

Franklin's life was marked by a profound commitment to science, yet her gender and untimely death underscored the tragic dimensions of her legacy.

Description: This episode explores how DNA detectives use scientific methods to solve crimes, highlighting the importance of DNA analysis in forensic science.

Description: Meet the DNA "detective" who played a crucial role in resolving a cold case that had stumped investigators for decades, showcasing the impact of DNA technology in justice.