# Trusting Science: Navigating Uncertainty in Research

Written on

Chapter 1: Understanding Scientific Certainty

The question of whether we should trust science arises from the inherent uncertainties within scientific research. If we were to wait for absolute proof before taking action, we would find ourselves paralyzed, unable to make any significant choices.

As Bertrand Russell, a renowned philosopher and mathematician, once stated, “When one admits that nothing is certain, one must also recognize that some things are more nearly certain than others.”

Recently, I discussed the potential dangers of marijuana and mentioned a critical caveat: “We lack firm conclusions on a lot of this.” A perceptive reader raised two valid questions: “What’s the purpose of sharing this information if the studies lack confirmation? Doesn’t this seem like an irresponsible way to disseminate information?”

My response highlights a stark reality: science never provides indisputable proof. However, this does not render a body of inconclusive research useless; rather, it indicates that our understanding can vary from tentative to robust, but not to the point of absolute certainty. This is why science communicators often use terms like "suggests," "shows," or "indicates" instead of "proves."

Scientific Uncertainty and Decision-Making

Carl Sagan once remarked, “Absolute certainty will always elude us.” Despite our yearning for certainty, the best we can hope for is a progressive enhancement of our understanding through learning from our missteps.

It is crucial not to dismiss rational scientific conclusions or widely accepted expert advice simply due to lingering uncertainties. In fact, relying on imperfect science to make informed decisions about health, the environment, or other significant topics is preferable to complete inaction. For example, if numerous individuals engage in a behavior they believe to be harmless (like using marijuana) and there is reasonable evidence suggesting they may be misinformed, it is far more prudent to present that evidence—even if it’s not yet conclusive—than to wait indefinitely for some elusive proof.

We routinely make decisions based on incomplete scientific knowledge. Many medications are effective despite a lack of complete understanding of their mechanisms. Millions of individuals take these potentially life-saving drugs, provided they have been shown to be reasonably safe. Similarly, although meteorologists cannot predict precisely when or where a hurricane will strike, sensible individuals evacuate when the best available science indicates a significant storm is imminent.

When responding to the reader about my marijuana discussion, I noted that scientific inquiry—especially in health and medicine—often evolves through investigations that yield incremental insights, leading to hypotheses that may later develop into tentative conclusions.

Further research, employing diverse methodologies and conducted by various researchers, is almost always necessary to establish a body of work that strengthens our conclusions. This principle applies across various health topics, including the effects of different behaviors and the suspected causes of various conditions. Ignoring the existing science—especially as it becomes increasingly solid—while waiting for elusive “absolute proof” would be imprudent.

The Incremental Nature of Scientific Inquiry

If we adhered to such logic, we would write very little about most diseases and conditions, and might still be unaware of the severe damage caused by tobacco or alcohol. A pertinent example: the old belief that a daily drink is beneficial was debunked in 2017. While we cannot definitively say that a daily drink is harmful to every individual, we can assert this claim with considerable confidence.

Advancing scientific knowledge requires a methodical approach, which is often misunderstood. Here are some fundamental principles:

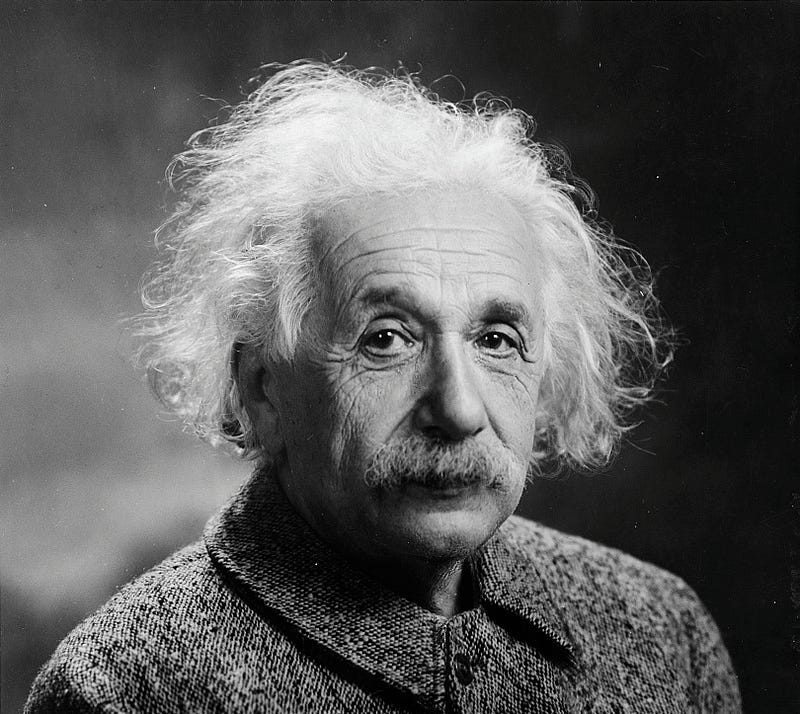

“The more I learn, the more I realize how much I don’t know.” — Albert Einstein

Scientific research typically begins with a hypothesis, which is more than a mere opinion; it is a testable proposition explaining a phenomenon. A hypothesis must be falsifiable, meaning it can be proven false.

You might assume that once sufficient evidence is gathered, a hypothesis becomes a theory, and a proven theory evolves into a law. However, this is a misunderstanding.

Hypotheses, theories, and laws represent different categories of scientific explanations, akin to apples, oranges, and kumquats. They differ in scope, not in the level of support they receive, as clarified by scientists at the University of California Museum of Paleontology.

The scientific investigation process generally follows these steps:

- Define a question and make predictions.

- Gather and analyze data (both existing and new).

- Draw conclusions or make reasonable conjectures.

- Await validation or refutation from additional research.

While this outline simplifies the scientific method, the reality is far more intricate. Scientific research is iterative and circular. Any worthwhile topic necessitates multiple research teams examining it from various perspectives and disciplines. Competent scientists continuously ask questions, test hypotheses, draw conclusions, and revisit each stage of the method. Science is not a linear process.

A theory, which differs significantly from a hypothesis, provides an in-depth explanation that may encompass several hypotheses and laws, along with numerous facts. Laws are considered established truths that explain phenomena like gravity or energy conservation, often represented mathematically. However, even laws can be refined as our understanding evolves.

The Essence of Scientific Inquiry

The objective of scientific inquiry is as much about disproving hypotheses as it is about proving them. Scientists enjoy challenging each other's findings, often rigorously testing hypotheses through replication or alternative methods to confirm or refute existing knowledge. This process is crucial for the effectiveness of science, albeit imperfect.

Science is inherently approximate. Scientists recognize and thrive on this imperfection. As Richard Feynman, a renowned physicist and Nobel Laureate, articulated:

“When a scientist doesn’t know the answer to a problem, he is ignorant. When he has a hunch about the result, he is uncertain. And when he is quite sure of the outcome, he is still in some doubt. Scientific knowledge comprises statements of varying certainty—some highly uncertain, some nearly certain, but none absolutely so.”

As a journalist focused on science and health, I do not advocate for science blindly. I am passionate about learning and sharing what we understand, serving as a connection between knowledgeable scientists and readers eager to learn more.

I am a hopeful skeptic, always eager to uncover the latest developments, while remaining vigilant for flaws in findings. This is why I produce articles that clarify what we currently know about various scientific topics, even when the evidence is not fully conclusive.

I take pleasure in debunking myths and reporting on discoveries that challenge longstanding beliefs. I also appreciate the incremental findings that suggest a growing consensus or remind us of the gaps in our knowledge. Sometimes, these insights lead to actionable advice, and other times they simply pique our curiosity.

Whether you are a science enthusiast or skeptical of its conclusions, my message is clear:

Healthy skepticism regarding incomplete or shaky science is vital. However, when a substantial body of evidence points toward a conclusion, or when multiple well-conducted studies from various research groups suggest a reasonable outcome, and when a consensus emerges among experts in the field, it is sensible to consider these findings while remaining open to further exploration. To outright dismiss scientific reasoning simply because it lacks absolute certainty is, in my view, unwise.

As we continue to delve into any subject—be it marijuana, Mars, earthquakes, or climate change—there will always be more stories to uncover. With each new study, our understanding will evolve, sometimes leading to surprising revelations.

Your support fuels my writing and reporting endeavors. To enhance your days, consider exploring my book: "Make Sleep Your Superpower." Additionally, if you are a writer, check out my Writer’s Guide newsletter.

Chapter 2: The Case for Trusting Science

The first video titled "Trust Science" is a BAD Idea explores the pitfalls of blind faith in scientific conclusions and emphasizes the necessity of critical thinking.

The second video, "Why Trust Science? - with Naomi Oreskes," discusses the historical context of scientific trust and the importance of evidence-based reasoning.